What You Need Is Motivation

Mid back-to-the-drawing-board, Midjourney

Before I wrote this essay, I tried writing another essay about management and culture and motivation and attention. I got to 5,000 words (that's 20 pages double-spaced!!) before I realized it was not good. From the ashes of that one arises this one.

Was it worth it? It was not. The last time I wrote 20 pages double-spaced, I was pulling an all-nighter in Van Pelt Library, the not-prettiest building on Penn's campus. Also wasn't worth it, but at least I turned that one in.

A-, if you wondered.

The vibe, as they say, is in shambles. Workers don't like working, companies don't like company-ing, no one is having fun, and the damages are in the trillions. We’re in a trough.

If we’re to find our way back out, the corporates must rediscover the lost art of motivating, and with "culture" on the wane, it's all up to the middle managers now.

Wants and needs

How do you motivate someone to do something outside their nature?

You begin by understanding needs. Then, either satisfy the needs of the target (thereby engendering gratitude, reciprocity, and eventually love) or deprive them of what they need (thereby engendering fear, eventually hate).

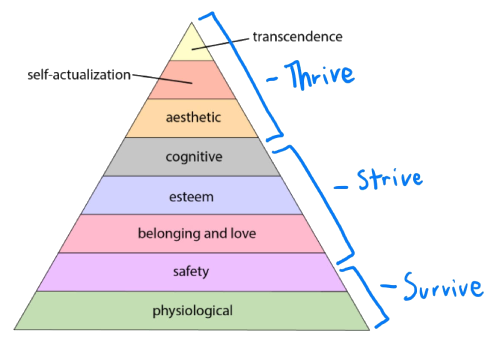

The most well-known framework on needs is Abraham Maslow's. Maslow, in his 1943 paper "A Theory of Human Motivation," introduced the model that would come to bear his name: "Maslow's hierarchy of needs."

Depending on which Wikipedia page you're reading, the hierarchy has between 5 and 8 tiers.

That many categories is too many for the modern attention span, so I’ve taken the liberty of collapsing into three tiers: Survive, Strive, and Thrive.

The pyramid shape is meant to confer that the lowest need must be met before the next "step" or tier can be considered. This feels intuitive: if you are threatening to deprive me of my life (physiological / Survive), I'm not worried about whether the Bauhaus couch you've tied me up on goes with the Hamadan rug in the entryway. This also explains why you wouldn't like me when I'm hungry: "belonging and love" take a back seat to "burrito."

In upper socioeconomic bands of developed societies, motivation maestros deal in the upper tiers. For the most part and for most people, the Survive needs are satisfied. Water, calories, and mates (biologically and in the British sense) are generally available. When that's true, we get to go to the next level of the game and wholly new ways to strive for achievement and be unhappy.

And where do motivation maestros and unhappy achievers meet?

The American business corporation.

Inside the American business corporation, the euphemism for "motivation" is "culture."

The job of culture must be motivation

Peter Drucker, influential business thinker and patron saint of management consultants, is credited with saying, "Culture eats strategy for breakfast."* In American parlance, when something eats something else for breakfast, it means the eater has dealt easily with the eaten. "You troubled me no more than my morning omelette."

In the corporate context, I think it means: the best strategy sucks if no one is putting their back into it. And as long as I’m talking about what I think, I think this is right. A motivated worker does more of the little things more of the time, and when you multiply by an entire (or even most of an) organization, you create places where people do work they are proud of.

When I was a young business boy in Silicon Valley in the boom-time Twenty-Teens (2013-2019), I heard this saying a lot, mostly from executives who were congratulating themselves for the amazing cultures they'd built.

These cultures did seem to provide strong motivational scaffolding at the appropriate Maslowian tiers to answer the question, "Why should I do it?"

The culture answered:

“Do it for the person next to you”

“Do it for your equity”

“Do it because we’ll take care of you”

“Do it because you're learning”

Culture is just motivation... at scale. When large groups of people are sufficiently motivated at the appropriate tiers, they create things that create legacies, like the Pyramids (physiological / Survive tier) or an app that captures your attention and resells it for a profit (esteem / cognitive / Strive tier).

Do it for the culture?

How is the culture doing today? From where I sit (on my butt, no lumbar support, curling more into my final shrimp form with each passing day), the power of the corporate culture to eat anyone's breakfast or motivate anyone on its own is near its nadir. The motivational scaffolding is crumbling, and they don’t make replacement parts like they used to.

Cynicism about corporate culture generally, and about Silicon Valley corporate culture specifically, is of the fashion right now.

Let’s examine some of the prior pillars:

“Do it for the person next to you" (belonging)

The zeitgeist is now that you should not regard your employer or your work team as part of your family. I love Salesforce for giving me the opportunity that started my career and then letting me hang around for 5 years, but they did come in for some deserved criticism when thousands of members of the ohana (no one gets left behind?) were deemed surplus to requirements.

“Do it for your equity” or "you're an owner too" (belonging / esteem)

(or “Here we are at this plucky technology start-up, it’s us against the world, we're pirates in the Jobsian mold: bolder, nimbler, taking potshots at the doddering navy. Learn faster, make a difference, run shit, all the way to the pot of gold!”)

The symbiotic relationship between VCs and startups created a lot of wealth, and I think a lot of meaning, for a while. Most of that wealth (who knows about the meaning) went to the VCs. Today, prospective startup employees understand that not every unicorn shoots rainbows out of its butt, that not every rainbow has a pot of gold at the end, and that your pot, as an employee, will be fun-sized.

“Do it because we’ll take care of you” (safety)

In the US, this doesn’t really exist anymore, and this particular piece of cultural messaging may feel outdated. But, it's included here because a lot of modern management theory came from the era where this was part of the deal, and I think people still seek the stability of large enterprises. Drucker is still widely cited (not just by me), his ideas are still widely influential, and he honed much of this thinking at GM in the 1940's, when paternalistic management and lifetime employment were still de rigueur. Of course, the corporation is no longer viewed as a caretaker or source of stability. Trillion dollar companies will not hesitate to jettison tenured employees in turbulent times.

"Do it because you're learning" (cognitive / self-actualization)

Look, I like learning a lot, and I do think it's something to be optimized for in a career. Unfortunately, I think it's become an excuse to pay people less, especially in ill-defined roles. It's kind of like, "I can't pay you in money, but I'll pay you in smiles." I like smiles, but if I'm going to be expected to smile back, then I expect to earn while I learn.

Zooming out a little bit, I think it would be disingenuous if I didn’t mention the expansion of remote work as a norm as a factor in the waning of corporate cultural power. Imagine the office as large private pool. Organizations used to control the water in which we swam, the temperature, the direction of flow, the depth. Today, we’re sitting in inflatable kiddie pools in our living rooms (at least I am). To pretend that remote work as a norm should have no bearing on culture and the organization’s ability to motivate… to pretend as much would be willfully obtuse.

So…

But so, the point is: disillusionment is the default. What are the implications of that?

I'll put it in terms that we can all understand: the implications are MONEY. Less money. Less money for everyone.

Gallup's recent flagship employee study alleges that just 33% of employees feel "engaged" (another corporate euphemism for "motivated") to the tune of $1.9T in lost productivity, annually. That's a T in that last sentence if you're reading quickly or skipping around — equal to 7% of 2023 US GDP.

Aside: maybe this is the answer to Robert Solow's famous quip about how computers are everywhere except the productivity statistics? Is there something about computer-based work that lends itself to more-than-usual alienation from the work itself, alienation that manifests as depressed productivity, thereby canceling out the obvious gains in communication and coordination that computers afford? I dunno!

Anyway, all this to say, in the absence of a culture (remember: motivation at scale) that is both clear and credible in its aims and promises, it’s up to you, middle managers, to do the motivating. A workforce turns its weary eyes to you.

Cometh the moment,

cometh the man(ager)

Even in the hey-day of “culture” and breakfast, it was known that you work for your manager more than you work for a company.

It was true then, it is true today, and it will be true until they replace middle managers with AI managers (which honestly may not be far off — I've heard that AI girlfriends are getting pretty good, although I've done no personal primary research on this topic, in case anyone or my real-life girlfriend was wondering).

It’s true because motivating begins with needs, and managers can respond to their team’s needs better than any top-down cultural architect. Recall that when we talk about motivation in a corporate context, we're talking about the higher-order needs, the ones in the Strive and Thrive categories. In these upper tiers, humans display far more individual differences than at the lower tiers, and this is a core reason why managers are the basis of corporate structural integrity.

What I mean is: we are all alike in our Survive-tier needs: food, water, some sunlight, some shade. We're basically plants all the way down. But the further up the hierarchy you have the privilege of going, the more individual differences you encounter. Strive and Thrive needs vary significantly from person to person. If that were not the case, if the higher needs were as simple as food and water and shade, setting up centralized motivation would be simple and effective, everyone would row in the same direction all the time, and we wouldn’t need managers.

Spare a thought for your neighborhood middle manager. They are derided in Dilbert, their incompetence explained at a systematic level by the Peter Principle, their archetype epitomized on screen by the hapless Michael Scott. The middle managers in our myths (and sometimes in our midst) look less like visionary leaders than bureaucrat flunkies. And look, much of the ridicule is deserved. Some managers, maybe too many, are bad.

But, for now and perhaps now more than prior, middle managers must exist because they are the ones best positioned to both understand the needs of individuals and motivate those individuals based on that understanding. They are the decentralized and distributed parts of the motivational machine that might survive the rust at the core.

It's very easy to be cynical about a faceless, distant "them." It's harder to be cynical about an interested, present one of "us." The people who can convince us that they are us and that we should do great work are the ones that corporations must identify and empower if they are to harness and coordinate our efforts. These are the people who should be managers.

For most people, the limiting factor on the quality of their work is not ability; it's motivation.

Lead us from this trough of disillusionment, middle manager.

The advice column section

To the executives I count among my readership: culture is who gets hired, fired, and promoted. Every other cultural signal pales in comparison to these people decisions.

If finance is all about what gets invested in, culture is all about who gets invested in. Companies can still invest in culture by investing in managers, the non-commissioned officers in Maslow’s Army, by promoting the right people into motivational positions, people who care about people, or at the very least, can passably pretend they do.

To the disillusioned majority, the 66%, I say this (because for some reason, every blog post has to end with some pithy nugget of advice):

Look not for the right company. Look not for the right culture. Both the chances and the cost of your disappointment are too high. Look instead for the right manager. Ultimately, it will be they who do or do not give you what you need.

Notes

*Whenever I hear this saying, I cannot help but remember one of the all-time great lines from one of the all-time great sports comedies, Happy Gilmore. Adam Sandler plays Happy, a down-on-his-luck hockey player who discovers a latent talent for golf. His nemesis is Shooter McGavin, an arrogant blue-blood professional golfer. They have the following memorable exchange:

Shooter: “You're in big trouble, pal. I eat pieces of shit like you for breakfast!”

Gilmore: “You eat pieces of shit for breakfast?”

Shooter: “... No!”

Works Cited

"Wikipedia Contributors. 'Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.' Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 28 January 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maslow%27s_hierarchy_of_needs."

Gallup. "In New Workplace, U.S. Employee Engagement Stagnates." Gallup, January 23, 2024, https://www.gallup.com/workplace/608675/new-workplace-employee-engagement-stagnates.aspx. Accessed 28 January 2023.

Thank you for reading.